In the heart of Bangkok’s administrative district, a quiet revolution is reshaping the landscape of public service infrastructure. The Government Complex on Chaeng Watthana Road is undergoing a historic transformation. Spearheaded by Dhanarak Asset Development Company Limited (DAD), the initiative redefines how a government facility can contribute to climate action, urban sustainability, and civic well-being. Branded under the vision “A Low Carbon City Working with Nature,” this project is poised to become a model for 21st-century urban development that harmoniously blends technology, ecology, and governance.

Since its inception more than two decades ago, the Government Complex has served as a central hub for over 50 public agencies, drawing an estimated 40,000 visitors and employees daily. Yet this sprawling site, covering 378 rai, has long borne the hallmarks of urban decay including concrete dominance, traffic congestion, and heat island effects. Now, a sweeping reimagination is rewriting its identity by shifting from a concrete island to a living, breathing ecosystem.

DAD President Dr. Nalikatibhag Sangsnit describes this transformation as a new social contract between development and nature. He states that the Government Complex is no longer just a collection of office buildings but is becoming an urban ecosystem that breathes and lives. According to him, this project represents a regenerative shift where the goal is not merely to restore the environment but to work actively with it.

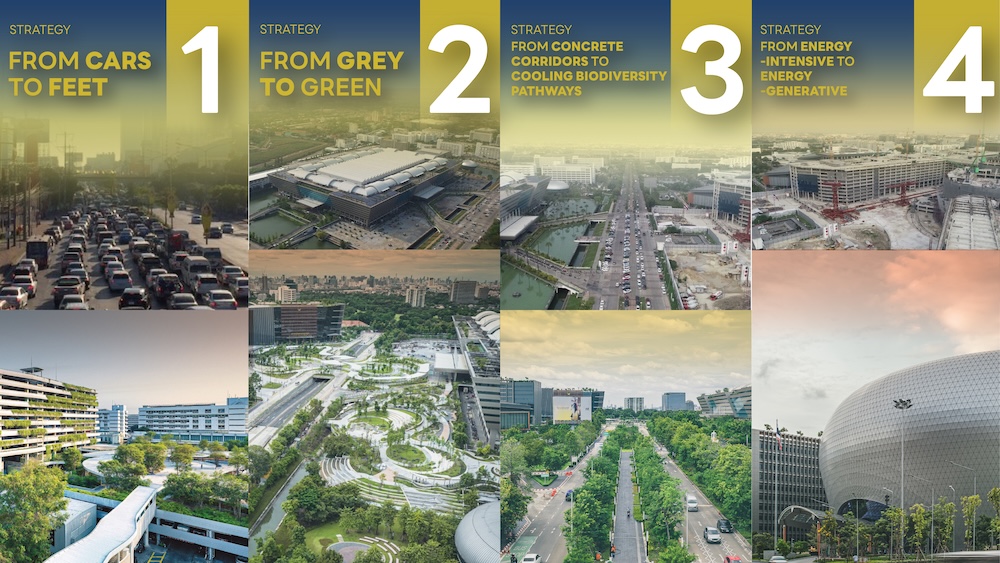

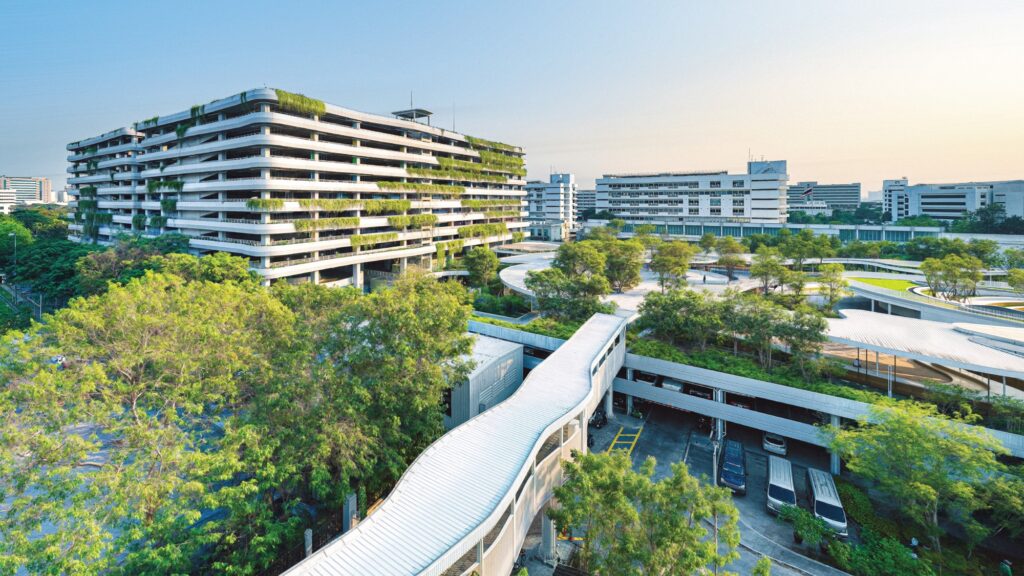

At the centre of this vision are four interconnected strategies that aim to rewire the Complex’s structure and function. The first centres on mobility and culture. Traditionally designed with cars in mind, the site is now pivoting toward pedestrian-friendly infrastructure. The recently completed 205-metre skywalk provides direct access from the Pink Line MRT to the complex. This is complemented by a fleet of electric shuttle buses that support car-free commuting. Roadways are being converted into community spaces known as Canopy Corridor Networks and B-C Hybrid Parks, which are shaded environments that blend pedestrian paths with accessible transit and foliage. This shift from cars to feet is more than infrastructure as it represents a cultural evolution.

The second transformation focuses on the environment. Under the concept of moving from grey to green, rooftops and parking lots are being reimagined as ecological zones. A key success under this strategy is the A–D Sky Park, an 8,000-square metre open-air community park located atop a building. It provides green respite in an urban area that was once barren. Parking facilities are also being redesigned into sponge parking systems which capture and recycle rainwater. This is a practical solution that aligns with Bangkok’s vulnerability to flooding. A previously underused 14-rai pond has been revitalised into the B-Park Urban Floating Oasis, which cools the area by up to nine degrees Celsius at ground level according to project data.

The third strategy is titled from concrete to biodiversity. Over 138 rai have now been dedicated to biodiversity corridors that include the planting of 5,500 native trees and the establishment of rain gardens and bioswales. These green corridors purify water, cool the air, and create new habitats for pollinators, birds, and butterflies. This effort aligns with findings by the World Economic Forum in 2024 that suggest urban biodiversity restoration can significantly lower city temperatures while improving ecological resilience.

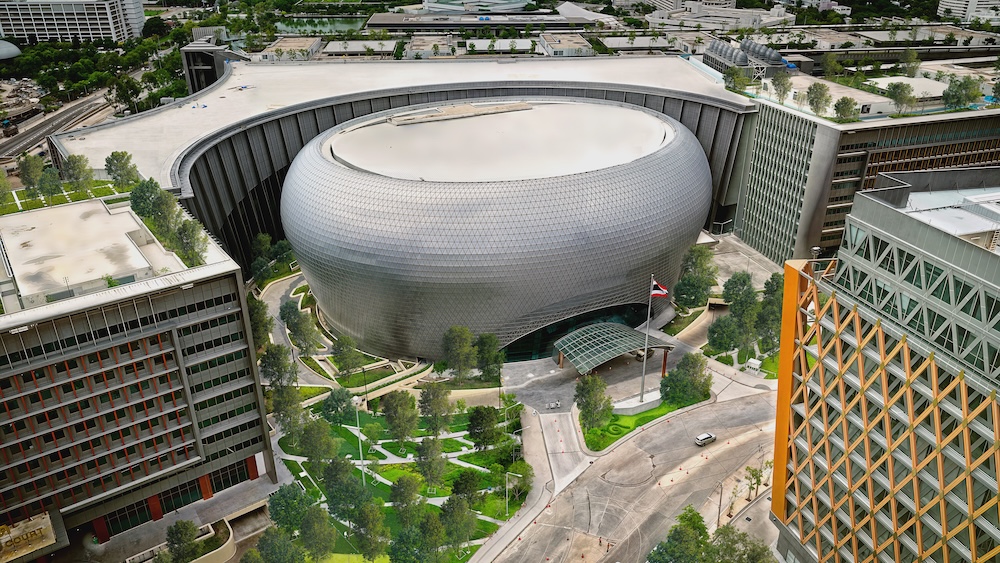

Energy is the fourth and perhaps most transformative element of the plan. Historically a power-intensive site, the Complex is being repositioned as a clean energy producer. Since 2016, solar installations across ten buildings have generated 3.9 million kilowatt-hours of electricity annually, saving more than 16 million baht each year. The project is now advancing to the next level with the development of an integrated energy storage system. This combines battery and hydrogen technologies to allow solar energy captured during the day to be used at night.

Leading this energy revolution is the Dhanaphiphat Building, which has been recognised as Thailand’s first Net Zero Energy Building. It has earned both DGNB Platinum and EDGE Advanced certifications. This building represents Thailand’s commitment to the Bio-Circular-Green Economy Model and supports the national goal of reaching carbon neutrality by the year 2050.

Dr. Nalikatibhag summarised this philosophy by stating that public administration can live in harmony with nature without sacrificing efficiency. He believes a low carbon city does not have to start with the private sector, and instead can begin with a shift in mindset within the public sector itself, evolving from a traditional building owner into a designer of social ecosystems.

Progress on the project is notable. As of December 2025, 89 percent of the redevelopment is complete. Green space has increased from 36 rai to 138 rai. This was achieved by replacing heat-retaining concrete with porous, water-absorbing surfaces. The updated landscape helps to combat urban heat and mitigates the risk of flooding during the monsoon season. Upon completion, the project is expected to serve as a replicable model for government facilities across the country.

The implications of this transformation extend far beyond the Chaeng Watthana site. In an era when cities are grappling with the realities of climate disruption, DAD’s vision challenges the conventional wisdom about public infrastructure. Government facilities are often seen as the least agile when it comes to adopting new technologies. Yet in this case, the public sector is acting as a pioneer by not only responding to climate change but modelling what resilience, innovation, and regeneration can look like.

Across the globe, adaptation to climate change remains a daunting task. In many countries, public infrastructure responds only after a crisis strikes. Bangkok’s approach is different. It is proactive and begins at the policy level, with implementation driven through design. The new identity of the Government Complex, which now blends administration with ecology, shows how cities can be shaped through foresight and intentionality.

International trends in sustainable urban planning provide useful comparisons. Singapore’s City in a Garden strategy and Paris’ 15-minute city model illustrate how other cities are pursuing climate adaptation and citizen wellbeing. Thailand’s example offers a regional perspective that considers the local climate, cultural patterns, and urban demands.

The transformation is also inclusive. New public green spaces offer benefits beyond aesthetics. These include shaded areas for walking, recreational spaces, and cooler zones that enhance the daily experiences of workers, residents, and commuters. This public access ensures that the benefits of the redevelopment are shared equitably.

Some may question the costs of such large-scale retrofitting. However, DAD reports that the long-term returns in reduced energy costs, lower maintenance expenses, and improved public health are significant. Furthermore, the initiative may attract new sources of funding through green bonds or impact investment funds that support sustainable development.

Thailand’s example offers lessons for the global community. In many cases, the public sector is overlooked in sustainability discussions. This project challenges that narrative by placing government-led infrastructure at the centre of the climate solution. The message is clear: transformation can begin at the core of public service.

As the final phase of construction nears completion, the Government Complex will move beyond symbolic gestures and become a functioning prototype. For a city like Bangkok, often criticised for its urban sprawl and environmental vulnerabilities, this is a major shift.

Urban renewal is frequently discussed in theory, but on Chaeng Watthana Road it is becoming a lived reality. The Government Complex is evolving from a dense urban block into a vibrant and sustainable ecosystem. This transition is not just about physical change. It reflects a deeper commitment to designing cities that are not only resilient but also inspiring.

In a world facing urgent climate challenges, Thailand’s approach provides both a roadmap and a message of hope. It confirms that within the bureaucracy there is space for innovation and leadership. Dr. Nalikatibhag sums it up best by stating that this is not simply about planting more trees. It is about planting the future of Thailand.

FAQs: Green Is the New Power – How Thailand’s Government Complex Became a Showcase for Sustainable Investment

Q1: What is the main goal behind the transformation of Thailand’s Government Complex?

A1: The primary goal is to convert the complex into a low-carbon, regenerative urban ecosystem that works in harmony with nature, supports clean energy, promotes biodiversity, and improves urban resilience.

Q2: Who is leading the redevelopment of the Government Complex?

A2: The redevelopment is being led by Dhanarak Asset Development Company Limited (DAD), a public organisation under Thailand’s Ministry of Finance.

Q3: How is the project addressing urban mobility and transportation?

A3: The project reduces reliance on private vehicles through a new 205-metre skywalk linking the MRT Pink Line to the complex, along with EV shuttle buses and redesigned green roadways called Canopy Corridor Networks.

Q4: In what ways has the complex incorporated green and public spaces?

A4: Initiatives like the 8,000-sq.m. A–D Sky Park and Sponge Parking systems turn rooftops and parking lots into ecological zones, while a redeveloped 14-rai pond became the B-Park Urban Floating Oasis that cools pedestrian areas by up to 9°C.

Q5: What role does biodiversity play in the redevelopment strategy?

A5: Over 138 rai have been transformed into green corridors with 5,500 native trees, rain gardens, and bioswales to purify water and provide habitats for birds, butterflies, and pollinators, enhancing ecosystem diversity.

Q6: How is the complex contributing to Thailand’s energy sustainability goals?

A6: Since 2016, ten buildings have produced 3.9 million kWh annually from solar panels, saving over 16 million baht per year. New energy storage systems using hydrogen and batteries will support clean energy use at night.

Q7: What is the significance of the Dhanaphiphat Building in this transformation?

A7: The Dhanaphiphat Building is Thailand’s first Net Zero Energy Building, certified DGNB Platinum and EDGE Advanced, showcasing advanced sustainable building technologies.

Q8: How far along is the project and what impact has it had so far?

A8: As of December 2025, the project is 89% complete and has expanded green space from 36 rai to 138 rai, replacing concrete with porous materials to reduce heat and flooding.

Q9: How does this project align with Thailand’s national environmental strategy?

A9: It supports the Bio-Circular-Green Economy Model and aims to help the country reach carbon neutrality by 2050, serving as a prototype for sustainable government infrastructure.

Q10: Why is this project considered a model for sustainable investment?

A10: The redevelopment delivers measurable environmental and economic benefits, demonstrating how public infrastructure can attract green financing and ESG-aligned investment.